The Impossible Workspace: How We Learned to Think About Thinking

Why we stopped fighting the brain's limits and started designing for them.

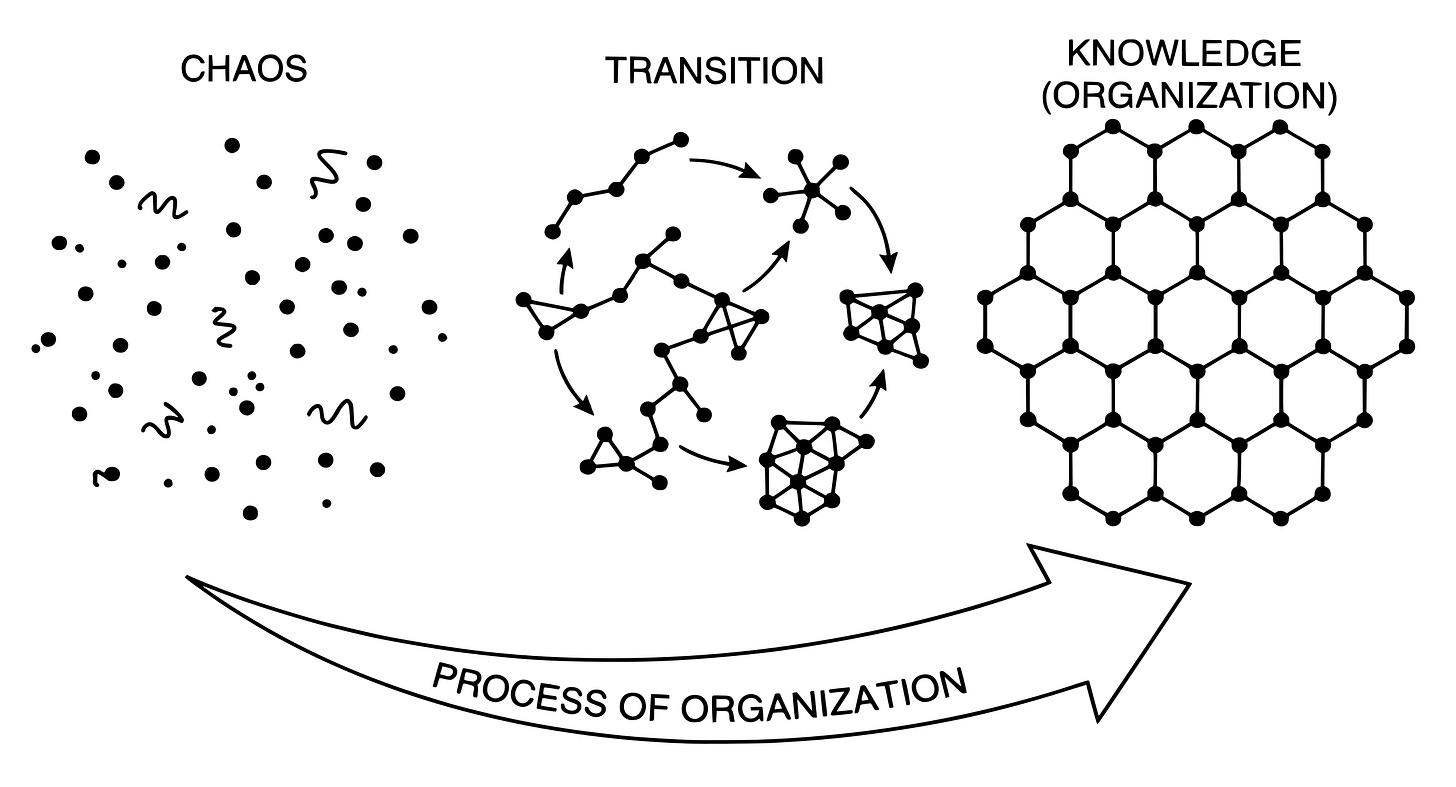

A Note from the Lab: At DataMind, we don’t believe “Intelligence” is magic. We believe it is a structure.

We spend our days engineering offline AI for students who have never touched a computer. To do this, we can’t just throw raw data at them. We have to understand the specific, biological limits of the human mind (The “Magical Number Seven”).

This essay is an excavation of those limits. It explains why most EdTech fails (it floods the working memory) and how we are building Project Khanyisa to respect the brain’s “Impossible Workspace.”

Your brain is doing something impossible right now.

You’re reading this sentence—which means you’re holding the beginning of it in your mind while processing the end. You’re accessing word meanings from long-term memory. You’re tracking grammatical structure. You’re integrating this with everything you’ve already read. And if you speak multiple languages, you’re somehow keeping all of them ready while using just one, able to switch mid-thought if needed.

Here’s the problem: your conscious attention can barely hold seven things at once. George Miller proved this in 1956 with his famous paper “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two.” Try remembering a ten-digit phone number you just heard. Try holding fifteen random words in your head. You can’t. We have severe, measurable limits.

So how do you read? How do you speak? How do bilinguals switch languages mid-sentence without their heads exploding?

This paradox broke psychology wide open in the 1960s, and the solution scientists invented—something called “working memory” operating within “modular” cognitive systems—became one of the most influential frameworks in cognitive science. But here’s what nobody tells you: these concepts didn’t emerge from pure observation of how minds work. They were constructed under specific pressures—technological metaphors, measurement constraints, bilingual anomalies, and institutional incentives that shaped what researchers could even think.

To understand what working memory really is, we need to excavate the layers beneath it. We need to dig through the historical context of when these ideas emerged, reconstruct the intent behind why researchers needed them, identify the forces that shaped their specific form, and track how they evolved from psychology to linguistics to bilingual research.

This is cognitive archaeology. Let’s start digging.

The Artifact: When Minds Became Workspaces

First, what are we even talking about?

Working memory is what cognitive scientists call the mental system that temporarily holds and manipulates information. It’s your cognitive scratchpad. When you’re doing mental math, following a conversation, or reading this sentence, you’re using working memory. Information flows in, gets processed, and either moves to long-term storage or gets discarded.

The key feature: it’s limited. Severely. You can only juggle a few items at once before the system overloads and you start dropping things.

Modularity is the idea that your mind isn’t one general-purpose processor but a collection of specialized systems—modules—each handling specific functions. There’s a language module, a vision module, a spatial reasoning module. They operate relatively independently, like departments in a factory, each with its own processes and capabilities.

Working memory, in this framework, becomes the coordinator—the system that shuttles information between modules, manages what’s active and what’s not, handles the switching and integration.

This is the standard story. You’ll find it in psychology textbooks, linguistics papers, neuroscience reviews. It seems clean, logical, almost inevitable.

But artifacts don’t explain themselves. They encode the time and place that created them. So let’s dig deeper—into the context of when minds became “modular” and why researchers started obsessing over “workspace capacity.”

The Context: When Machines Started Thinking

To understand why we talk about working memory and modules, we need to travel back to the mid-20th century. Specifically, to the 1950s and 60s—the era of the cognitive revolution.

Before this period, psychology was dominated by behaviorism. Behaviorists believed you couldn’t scientifically study thoughts, only observable behavior. The mind was a “black box”—stimulus goes in, response comes out, and what happens in between is unknowable speculation. Talking about “mental processes” was considered unscientific, almost mystical.

Then several things happened at once.

The Computer Revolution: The first digital computers emerged in the 1940s. Engineers built machines that took input, processed information, stored data, retrieved it, made decisions, and produced output. Suddenly, there existed a non-human, entirely physical system that did things that looked suspiciously like “thinking.”

This changed everything. If machines could process information, maybe minds could too—and maybe we could study mental processes scientifically by treating them like computational processes. Input, processing, output. Storage, retrieval, manipulation. The mind-as-computer metaphor was born.

Information Theory: In 1948, Claude Shannon published his mathematical theory of information transmission. He quantified how much information could flow through a channel, how noise degrades signals, how encoding affects transmission capacity. This gave researchers mathematical tools to ask new questions: How much information can humans process at once? What’s the “bandwidth” of human cognition? Where are the bottlenecks?

World War II Pressure: Military research desperately needed to understand human performance under stress. Fighter pilots, radar operators, cryptographers—all faced information overload. How much could a human handle before making fatal errors? This wasn’t philosophical curiosity; lives depended on it. The military poured funding into research on human attention, perception, and information processing.

These pressures converged to create a new paradigm. The mind could be studied scientifically—not as a mysterious black box, but as an information-processing system with measurable capacities and constraints.

But here’s the crucial archaeological insight: the mind-as-computer metaphor wasn’t chosen because it perfectly described reality. It was adopted because computers existed as working models, because information theory provided mathematical tools, and because military funding rewarded quantifiable research on human cognitive limits.

The metaphor that shaped cognitive science came from the technology available, not from pure observation of minds.

The Intent: Solving the Capacity Paradox

Now let’s reconstruct the original problem these frameworks were designed to solve.

Researchers quickly discovered that humans have severe information-processing limits. Miller’s “seven plus or minus two” was just the beginning. Studies showed:

People can only track a few objects at once

Short-term memory decays in seconds without rehearsal

Attention bottlenecks prevent multitasking

Reaction times increase with task complexity

We’re shockingly limited. And yet...

We read complex sentences. We follow conversations in noisy rooms. We drive cars while talking. We navigate cities while listening to music. We do incredibly complex things that should overwhelm our tiny capacity limits.

This was the capacity paradox: If we’re so limited, how do we function at all?

Early answers were unsatisfying. Maybe we’re just really good at rapid switching? Maybe practice expands capacity? These explanations felt like band-aids on a deeper mystery.

Then researchers started thinking modularly. What if different cognitive functions had their own specialized processing units—their own local workspaces? Language processing wouldn’t compete with visual processing for the same limited resource. Each module could have its own capacity, its own operating principles, its own memory systems.

Working memory wouldn’t be one general scratchpad but a coordinator managing multiple specialized workspaces. When you’re reading, the language module uses its own processing capacity while the visual system handles the text on the page. Working memory coordinates them, but they don’t compete for the same seven slots.

This solved multiple problems simultaneously:

Explained capacity paradoxes: We’re limited in some ways but not others because different modules have different limits.

Made cognition measurable: You could study modules independently, testing each system’s capacity separately.

Aligned with brain structure: Different brain regions specialize in different functions—visual cortex, auditory cortex, Broca’s area for language. Modularity mapped onto neuroscience.

Satisfied computational modeling: Modular systems are easier to simulate. Programmers know you don’t build one giant function; you build specialized modules that communicate through interfaces.

The intent wasn’t just explanatory—it was pragmatic. Modular frameworks made cognitive science doable. They transformed vague questions (”How do minds work?”) into testable hypotheses (”What’s the capacity of the phonological loop?”).

The Pressure Layer: Forces That Shaped the Theory

Now we dig into the richest archaeological layer: the pressures. What forces shaped how we think about working memory and modules? Why these specific forms and not others?

Pressure One: The Measurement Constraint

Science requires measurement. Behaviorism dominated precisely because behavior is measurable—you can count lever presses, time responses, observe actions. When cognitive scientists wanted to study mental processes, they faced intense pressure to operationalize their concepts.

You can’t get published saying “thinking feels complex.” You need numbers. Quantifiable results. Statistical analyses.

Working memory became defined by capacity limits because capacity could be measured. How many digits can you recall? How many words? How long before memory decays? These questions have numerical answers. They generate graphs, correlations, publishable data.

This created a self-fulfilling prophecy: researchers studied aspects of cognition that fit their measurement tools, and aspects that didn’t fit got ignored or marginalized.

Fossil pattern from astronomy: Early astronomy focused intensely on celestial mechanics—planetary orbits, eclipse predictions, gravitational calculations. Why? Because these were mathematically tractable. You could measure positions, calculate trajectories, make predictions.

Meanwhile, equally important questions—What are stars made of? How do they generate light? Why are there different colors?—got ignored for centuries. Not because astronomers didn’t care, but because they lacked the tools to measure stellar composition. Only when spectroscopy emerged in the 1800s did stellar chemistry become scientific.

Similarly, working memory research focused on capacity limits not necessarily because capacity is the most important aspect of our cognitive workspace, but because capacity was measurable with 1960s-70s methodology.

What got ignored? Flexibility. Context-sensitivity. The qualitative experience of thinking. How working memory interacts with emotion, motivation, cultural knowledge. These weren’t measurable, so they became secondary concerns—or were treated as “noise” to be controlled away.

The tools shaped the science. The questions we asked were constrained by what we could count.

Pressure Two: The Computational Metaphor

Computers process information in modules. A computer’s memory system is separate from its CPU. Storage is distinct from retrieval. Programs run in isolated processes that don’t interfere with each other (ideally). You can upgrade the graphics card without rewriting the operating system.

This metaphor was incredibly productive. It generated testable predictions, inspired experiments, shaped entire research programs. But it also constrained thinking in subtle ways.

Brains aren’t actually computers. Neural networks are massively parallel, not serial. They’re probabilistic, not deterministic. They’re context-dependent in ways that defy clean modular boundaries. Neurons don’t respect the kind of information-theoretic separation that computer modules do.

Fossil pattern from urban planning: In the 1950s-60s, urban planners embraced “functional zoning”—separate residential, commercial, and industrial zones. Each area optimized independently. Residential zones: quiet, green, family-friendly. Commercial zones: dense, efficient, car-accessible. Industrial zones: isolated, noisy, away from housing.

This seemed brilliantly rational. Why mix incompatible functions? Let each zone specialize.

The result? Car-dependent sprawl. Dead streets after business hours. Loss of community. Destroyed neighborhood ecosystems. Turns out real cities function as integrated systems where residential, commercial, and social functions constantly interact. The modular model looked good on paper but missed emergent properties of the whole system.

Jane Jacobs, in her 1961 book _The Death and Life of Great American Cities_, demolished functional zoning by showing how vibrant neighborhoods required mixing, overlap, and “messiness”—exactly what the modular model tried to eliminate.

Similarly, strict cognitive modularity might be oversimplifying how brain regions actually interact. They don’t operate in isolation; they’re constantly communicating, influencing each other, creating emergent patterns that don’t reduce to individual module functions.

But the computational metaphor encouraged researchers to think in terms of isolated modules with clean boundaries—because that’s how computers work, and computers were the available model.

Pressure Three: The Bilingual Anomaly

Here’s where the archaeological dig gets really interesting. Here’s where working memory theory hit a wall—and had to evolve.

If language is a module, what happens when you have two languages?

Early theories treated this like a radio dial: bilinguals must “select” one language and suppress the other. You switch channels completely. One language active, one dormant.

This seemed logical. It aligned with modular thinking. It matched computational models where you load one program at a time.

But real bilingual behavior shattered this model completely.

Code-switching: Bilinguals mix languages mid-conversation, mid-sentence, even mid-word. “Voy al store para comprar milk.” This happens effortlessly, without apparent cognitive strain, without “switching costs” that early theories predicted.

Metalinguistic awareness: Bilinguals often show enhanced ability to think about language structure itself—grammar rules, word meanings, linguistic patterns. They treat language as an object of analysis more readily than monolinguals.

Translation and interpreting: Professional translators hold both languages simultaneously active, mapping between them in real time. They’re not switching channels; they’re running both channels at once.

Crosslinguistic influence: One language constantly affects the other. Pronunciation bleeds across. Grammar structures transfer. Vocabulary creates hybrids. The languages aren’t isolated modules; they’re interacting systems.

These phenomena created massive pressure on modular models. If modules are isolated, how does code-switching work? If working memory is capacity-limited, how do interpreters juggle two entire linguistic systems? If each language is a separate module, why does metalinguistic knowledge increase?

The bilingual brain wasn’t behaving like a modular computer. It was behaving like something else entirely.

Fossil pattern from software architecture: Early computer programs were monolithic—one giant block of code doing everything. When developers needed programs to handle multiple languages (French, German, Japanese interfaces), this became a nightmare. You couldn’t just “add” another language; you had to rebuild everything, hardcoding each language separately.

This pressure drove the evolution of plugin architectures. Modern software uses APIs, dynamic loading, modular components that can be swapped without recompiling the whole program. The system doesn’t just switch between languages; it manages them as coordinated, interacting modules that share resources.

Bilingual research forced cognitive scientists down a similar evolutionary path. Working memory couldn’t just be a passive storage system with fixed capacity. It had to be an active coordinator—a cognitive operating system managing multiple linguistic apps, handling their interactions, dynamically allocating resources.

The bilingual anomaly didn’t disprove modularity, but it forced modularity to evolve. Rigid boxes became flexible, interacting systems. Capacity limits became dynamic resource allocation. Working memory transformed from a warehouse into an air traffic control system.

Pressure Four: The Institutional Incentive Structure

Let’s excavate a layer researchers rarely acknowledge: academic politics.

Cognitive science as a discipline needed to establish legitimacy in the 1960s-70s. It was fighting on multiple fronts:

Behaviorism dismissed cognitive approaches as unscientific “mentalism”

Neuroscience focused on brain hardware, treating psychological theories as irrelevant speculation

Linguistics (especially Chomsky’s approach) studied language structure abstractly, without caring about psychological reality

Computer science built AI systems without consulting psychologists

To survive as a distinct discipline, cognitive science needed:

Distinctive methodology (different from behaviorism’s stimulus-response)

frameworks (not just data collection)

Practical applications (to attract funding)

Quantifiable results (for publication and career advancement)

Modular frameworks delivered all of this.

They distinguished cognitive science from behaviorism (internal mental structures matter). They provided testable theories (modules make specific predictions about interference, capacity, processing speed). They connected to practical concerns (education, language learning, cognitive training, human-computer interaction). They generated measurable outcomes (memory span tests, reaction time studies, neuroimaging that could “light up” specific modules).

Researchers who framed their work within modular, capacity-focused frameworks got published in prestigious journals. They got grant funding from NSF and NIH. They got tenure. They built successful careers.

Researchers who pursued questions that didn’t fit this framework—qualitative studies of thinking, phenomenological approaches, cultural variations in cognition—struggled to publish, struggled to get funding, didn’t build research empires.

This created selective pressure—like natural selection, but for ideas. Theories that fit institutional incentives survived and reproduced through graduate students, citations, research programs. Theories that didn’t fit the incentive structure died out, even if they explained some aspects of cognition better.

Fossil pattern from evolutionary biology: In the 19th century, naturalists debated whether species were fixed (creationism) or mutable (evolution). Darwin’s theory won not just because it explained data better, but because it fit the Victorian cultural context: competitive struggle, gradual progress, natural hierarchy, variation and selection.

Alternative theories—like Lamarckism (inheritance of acquired characteristics) or saltationism (evolution through sudden jumps)—explained some data equally well but didn’t resonate with Victorian values. They lost the institutional competition.

Similarly, the Modular Cognition Framework succeeded partly because it fit the institutional ecology of late-20th-century cognitive science. It aligned with available technologies (computers), measurement tools (reaction times, memory tests), funding priorities (applied research, quantifiable outcomes), and career incentives (publish or perish).

This doesn’t make it wrong. But it does mean the framework’s dominance reflects institutional pressures as much as empirical truth.

The Evolution: How the Concept Mutated Across Disciplines

Now let’s track how “working memory” evolved as it jumped from psychology to linguistics to bilingual research. Each field adapted the concept to solve its own problems, creating fascinating mutations.

In Psychology: Working Memory as Capacity

The classic model came from Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974. They proposed working memory had specialized components:

Phonological loop: Handles verbal and acoustic information (the voice in your head when you rehearse a phone number)

Visuospatial sketchpad: Processes visual and spatial information (mental rotation, imagining routes)

Central executive: Coordinates attention, switches between tasks, manages the other systems

The focus was on capacity limits. How much could each component hold? What interfered with what? How did information decay?

The pressure here: Experimental psychology needed operationalizable constructs. You can test capacity. You can measure it with digit span tasks, dual-task paradigms, interference studies. This generated decades of publishable research.

In Linguistics: Working Memory as Syntactic Enabler

When linguists adopted working memory, they cared less about raw capacity and more about how it enables sentence processing.

Noam Chomsky’s transformational grammar required mental operations—moving phrases, embedding clauses, tracking dependencies across long distances. How do you understand “The dog that the cat that the rat bit chased died”? You need to hold sentence structure in memory while performing grammatical computations.

Working memory became the workspace for grammatical operations. Capacity mattered, but what really mattered was the types of operations the system could perform—stacking, recursion, long-distance dependencies.

The pressure here: Linguistic theory needed to connect “competence” (abstract grammatical knowledge) to “performance” (actual language use in real time). Working memory bridged this gap. It explained why some grammatically correct sentences are nearly impossible to understand—they exceed working memory’s operational capacity, not its storage capacity.

In Bilingual Research: Working Memory as Language Coordinator

By the 1990s-2000s, working memory had mutated again. Now it wasn’t just storage capacity or syntactic workspace—it was a **dynamic coordination system** managing multiple linguistic systems simultaneously.

Bilinguals don’t just use working memory; they use it to:

Suppress one language while using another (language control)

Switch between languages mid-thought (code-switching)

Hold both languages active during translation (simultaneous activation)

Monitor which language is appropriate in which context (metalinguistic awareness)

Manage interference when languages share similar words or structures (crosslinguistic influence)

Working memory transformed from a passive container into an active manager—a cognitive traffic controller juggling multiple systems in real time.

The pressure here: Bilingualism research needed to explain phenomena that didn’t exist in monolingual models. Code-switching without switch costs? Couldn’t be just passive storage. Metalinguistic awareness? Couldn’t be just capacity limits. The bilingual data **forced** working memory theory to become more sophisticated, more dynamic, more executive.

Fossil pattern from air traffic control: Early aviation had simple rules: planes flew fixed routes at fixed altitudes. As traffic increased, this system broke down catastrophically. Controllers needed to dynamically coordinate multiple aircraft, constantly updating flight paths in real time, managing priorities, preventing conflicts.

The system evolved from rigid procedures to flexible, adaptive, real-time coordination—exactly what working memory had to become to explain bilingual cognition.

The Synthesis: What the Archaeology Reveals

Let’s integrate all the layers. What does this excavation tell us about working memory that the surface understanding couldn’t?

The documented concept: Working memory is a limited-capacity system that temporarily holds and manipulates information, operating within a modular cognitive architecture.

The historical context: The concept emerged in the 1960s-70s during the cognitive revolution, when computers provided a metaphor for mental processes and information theory provided mathematical tools.

The original intent: Researchers needed to explain how capacity-limited humans accomplish complex cognitive tasks. Modularity solved this by distributing functions across specialized systems.

The shaping pressures:

Measurement constraints favored capacity-focused definitions

Computational metaphors encouraged modular architectures

Bilingual phenomena forced flexibility and dynamic coordination into the model

Institutional incentives rewarded frameworks that generated testable, publishable results

The evolutionary path: Working memory mutated from a simple capacity construct (psychology) to a syntactic workspace (linguistics) to a multilingual coordinator (bilingual research), each discipline adapting it to solve their specific problems.

The deeper truth: Working memory isn’t a “natural kind” we discovered in the brain—it’s a conceptual tool we constructed under specific historical, technological, and institutional pressures.

This doesn’t make it wrong. It makes it contingent. The framework works—it explains data, generates predictions, guides research. But it works because it was designed to fit the available tools, metaphors, and institutional structures.

Understanding this archaeology reveals why certain aspects of cognition get emphasized (capacity limits, measurable interference) while others get marginalized (subjective experience, cultural variation, emotional integration). It’s not that researchers are biased or incompetent—it’s that the pressures shaping research create systematic blind spots.

The Beginner’s Takeaway: What This Means for You

If you’re encountering these ideas for the first time, here’s what matters:

Don’t mistake the map for the territory. When scientists talk about “working memory capacity” or “cognitive modules,” they’re using conceptual tools—powerful, useful tools—but tools nonetheless. The brain doesn’t have a component labeled “working memory” any more than the economy has a physical object called “GDP.” These are constructs that help us think and measure.

Understand the pressures behind the science. Every scientific concept is shaped by what’s measurable, what’s fundable, what’s publishable, what metaphors are culturally available. Ask: What couldn’t this theory explain? What did it ignore because it was unmeasurable or institutionally unrewarded?

Appreciate how bilingualism forced evolution. The most interesting aspect of this archaeology is how bilingual brains broke the simple models. Bilinguals don’t just “use” working memory—they expose its flexibility, its dynamic coordination abilities, its integration across supposedly separate modules. If you want to understand how cognition really works, study the edge cases that break the standard models.

Recognize that capacity limits might be artifacts. Working memory shows up as severely limited in lab tests—seven items, rapid decay, terrible multitasking. But bilinguals code-switching in natural conversation don’t seem capacity-limited at all. They fluidly juggle languages, access multiple grammars, manage complex interactions without apparent strain.

Maybe capacity limits are real fundamental constraints. Or maybe they’re measurement artifacts—byproducts of **how** we test working memory (artificial tasks, isolated stimuli, decontextualized recall) rather than fundamental properties of cognition in natural contexts.

The archaeology can’t decide this question. But it can make you appropriately skeptical of clean, simple answers.

Look for fossil patterns everywhere. Once you start seeing how concepts migrate across fields, you can’t unsee it. The mind-as-computer metaphor. The factory model of modularity. The air traffic control analogy for bilingual coordination. These aren’t just teaching aids—they’re archaeological evidence of the technological and cultural context that shaped cognitive science.

When the dominant technology changes, the metaphors change. When AI shifts from rule-based systems to neural networks, cognitive theories will shift too. We’re already seeing it—renewed interest in parallel processing, distributed representations, emergent properties. The next generation’s “working memory” will look different because the pressures shaping it are different.

Closing Reflection: Ideas as Artifacts

We started with a simple question: How do our minds juggle complex tasks despite severe capacity limits?

We excavated through five archaeological layers to find the answer—or rather, to find how the answer was constructed.

The artifacts: Working memory, modularity, capacity limits—documented in thousands of papers.

The context: The cognitive revolution, when computers made minds scientifically accessible.

The intent: Solving the capacity paradox while making cognition measurable.

The pressures: Measurement constraints, computational metaphors, bilingual anomalies, institutional incentives.

The evolution: Psychology’s capacity focus → linguistics’ syntactic workspace → bilingualism’s dynamic coordinator.

What we discovered: Working memory isn’t a discovered fact about brains—it’s a constructed concept shaped by historical circumstances, available technologies, methodological constraints, and the career incentives of researchers.

This doesn’t diminish the achievement. The framework genuinely explains mountains of data. It guides research, informs education, helps people understand their cognitive strengths and limitations.

But understanding its archaeology prevents us from reifying the model—from mistaking our current best framework for ultimate truth. Every theory is a fossil, recording not just the phenomenon it explains but the pressures that shaped the explanation.

The breakthrough insight: The bilingual brain didn’t just provide data for working memory theory—it forced working memory theory to evolve. Code-switching, metalinguistic awareness, effortless language coordination—these phenomena couldn’t be explained by simple capacity-limited modules. They demanded a more sophisticated model: dynamic coordination, flexible resource allocation, active management rather than passive storage.

The bilinguals were the anomaly that cracked the framework open and revealed what was missing.

This is how science actually works. Not through steady accumulation of facts, but through encounters with phenomena that break existing models and force reconstruction. The messiest data—the stuff that doesn’t fit—is often the most valuable.

So here’s your takeaway: When you learn about working memory, or cognitive modules, or any scientific concept, don’t just absorb the definition. Ask: What pressures shaped this idea? What does it explain well? What does it struggle with? What phenomena might force it to evolve next?

That’s cognitive archaeology. Not just studying what we know, but excavating how we came to know it—and recognizing that the excavation process itself reveals knowledge we didn’t know we had.

The next breakthrough won’t come from refining current models. It’ll come from finding the phenomenon that breaks them—the way bilingualism broke simple modularity.

We keep digging. The best fossils are still buried.