Ideas Are Like Fish: An Archaeological Excavation of Creativity's Most Persistent Metaphor

"Reverse-engineering the 'source code' of inspiration—tracing the fishing metaphor from Ancient Buddhism to David Lynch."

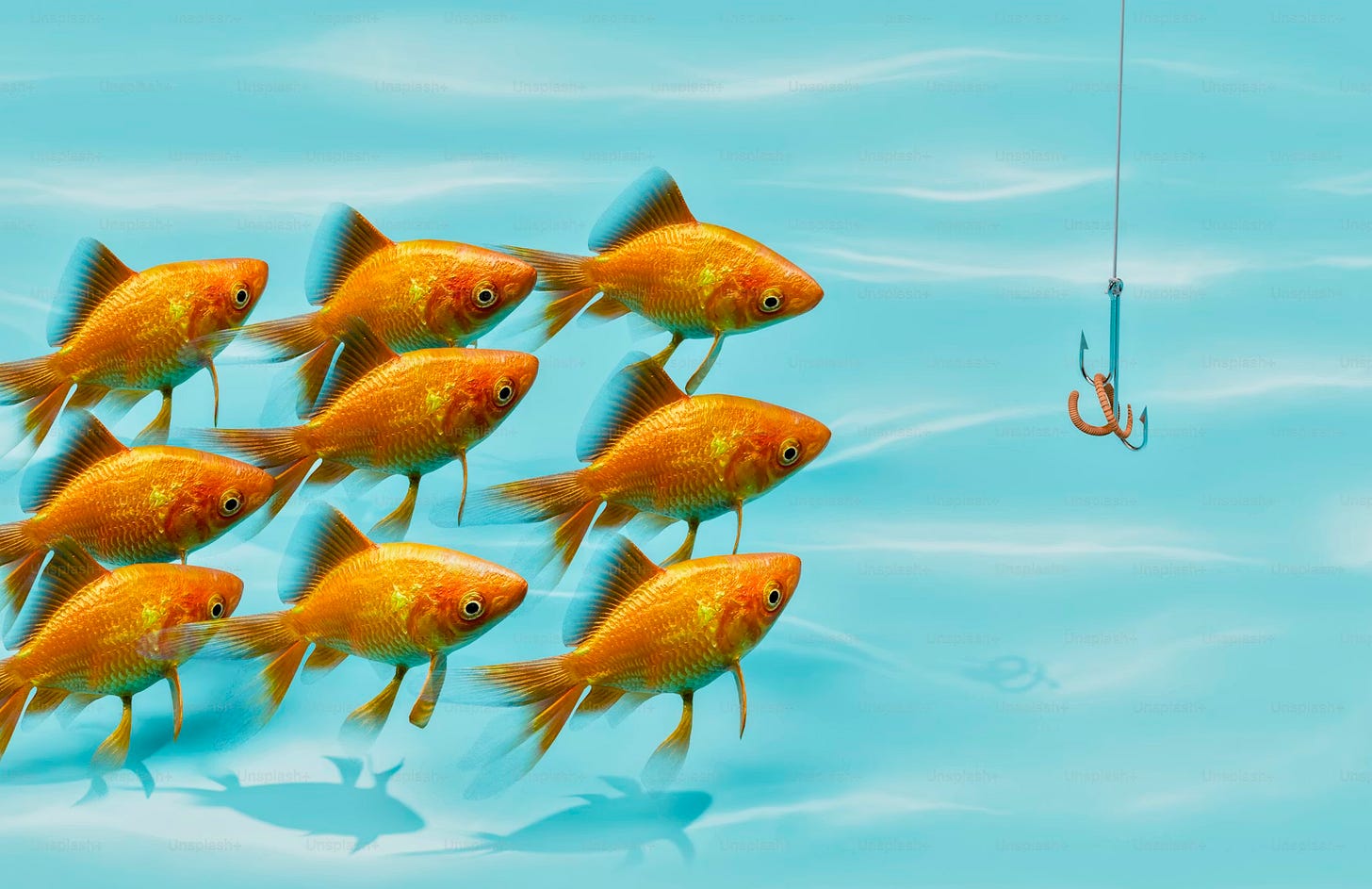

You’re sitting at your desk, mind blank, waiting for inspiration. Someone advises: “Don’t force it. Ideas are like fish—you have to be patient, let them come to you.” You nod, feeling the metaphor’s truth. But wait. Why fish? Why not birds, or seeds, or lightning? And why does this particular comparison feel so intuitively correct that it appears across cultures, centuries, and contexts—from Buddhist meditation halls to Hollywood director’s chairs to Silicon Valley brainstorming sessions?

The answer isn’t obvious. It’s buried.

This metaphor isn’t just a cute comparison. It’s an archaeological artifact—a fossilized record of humanity’s evolving relationship with the mind itself. By excavating its layers, we’ll uncover not just where this metaphor came from, but what it reveals about how we understand consciousness, creativity, and the very nature of thought.

Let’s begin the dig.

The Artifact Layer: Where Fish Swim in Our Discourse

First, we catalog the documented appearances.

Modern Canon (20th-21st Century):

David Lynch, “Catching the Big Fish” (2006): The filmmaker describes Transcendental Meditation as diving deep to catch bigger ideas: “If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper.”

Steven Pressfield, “The War of Art” (2002): Describes the creative process as baiting hooks for inspiration, waiting for the strike.

Elizabeth Gilbert, “Big Magic” (2015): Ideas as autonomous entities swimming through a collective creative ocean, occasionally choosing an artist to inhabit.

Academic Appearances:

Cognitive psychology papers (1990s-present): “Fishing for memories,” “idea generation as foraging”

Innovation literature : “Ideation pools,” “fishing for insights in data streams”

Eastern Philosophy:

Buddhist teachings (ancient-present): Mind as ocean, thoughts as fish swimming through awareness

Taoist texts: Wu Wei (effortless action) often illustrated through fishing metaphors

What’s documented: The metaphor appears most frequently in creative instruction, meditation guidance, and cognitive science. Notably, it’s almost always framed as advice about receptivity rather than active pursuit.

But documentation only tells us the metaphor exists. To understand why it exists, we must dig deeper.

The Context Layer: When Minds Became Oceans

Let’s reconstruct the intellectual landscape where this metaphor first took form.

Ancient Greece: The Invention Model (5th-4th Century BCE)

The Greeks didn’t fish for ideas—they received them. The Muses, divine entities, gave inspiration. Homer begins the Odyssey: “Sing to me, O Muse...” Plato’s Ion describes poets as possessed, channeling divine madness.

Crucially, the Greek word heuriskein (to find/discover) relates to our “eureka,” but it implied uncovering what already exists, not catching something elusive. The metaphor wasn’t fishing—it was mining. Ideas were buried treasures, not swimming prey.

Cultural context: A hierarchical cosmos where knowledge flows downward from gods. Humans don’t hunt; they receive.

Medieval Christianity: Passive Receptivity (5th-15th Century CE)

Medieval mystics described contemplation as waiting for God’s grace. Teresa of Avila’s “Interior Castle” (1577) uses water metaphors extensively—but the water is given (divine infusion), not fished from. The mind is a vessel to be filled, not an ocean to be fished.

Cultural context: Religious frameworks where human agency in inspiration is suspect (pride, heresy). You don’t catch God’s thoughts; you humbly receive them.

The Romantic Turn: Nature as Source (18th-19th Century)

Romantics like Wordsworth and Coleridge shifted the source from divine to natural. Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” came in an opium dream—ideas arising from the unconscious, not heavens. But the metaphor remained botanical/geological: ideas as seeds, springs, eruptions.

Wordsworth’s “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” suggests volcanic imagery, not aquatic.

Cultural context: Scientific revolution undermined divine inspiration, but mechanistic psychology hadn’t emerged. Nature replaced God as the creative source.

Early 20th Century: The Unconscious as Ocean

Here’s the pivot point.

Freud’s “The Interpretation of Dreams” (1899) popularized the iceberg metaphor: consciousness is the tip, unconscious the vast submerged mass. Jung expanded this with the “collective unconscious”—a shared psychological ocean connecting all humans.

Suddenly, the mind had depth. And depth suggested water. And water contained... fish.

Why the metaphor emerged NOW:

1. Psychological topography: Freud/Jung gave the mind spatial structure (surface/depth), making aquatic metaphors apt

2. Eastern philosophy influx: 1950s-60s brought Zen Buddhism to the West (Suzuki’s writings, Beat poets). Buddhist fish-mind metaphors cross-pollinated

3. Counterculture meditation boom (1960s-70s): Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation (TM) movement—which David Lynch practices—explicitly used diving/fishing metaphors

The convergence: Depth psychology + Eastern meditation + countercultural search for altered consciousness = ideas as fish in the ocean of mind.

This wasn’t inevitable. It required specific historical pressures.

The Intent Layer: The Problem This Metaphor Solved

What was this metaphor for? What question did it answer that previous models couldn’t?

The Central Paradox of Creativity

By the mid-20th century, creativity research faced a maddening contradiction:

Observation 1: You can’t force great ideas. Trying too hard produces mediocrity.

Observation 2: You can’t just wait passively. Ideas require preparation, practice, immersion.

The paradox: Creativity requires simultaneous effort and surrender.

Previous metaphors failed here:

Divine inspiration (too passive—what about the work?)

Invention/construction (too active—what about the “aha!” moments?)

Discovery (close, but implies ideas are stationary, waiting to be found)

Enter fishing.

Fishing is the perfect blend of active and passive:

Active components: You choose where to fish (which mental waters), prepare bait (study your craft), cast lines (sit down to work), remain alert (mental readiness)

Passive components: You can’t control when fish bite, can’t force them to surface, must wait patiently, need luck

The intent revealed: This metaphor solved the creativity instruction problem. How do you teach something that requires both discipline and letting go? You tell students: “Fish for ideas.”

It’s actionable (go to the water, cast your line) yet acknowledges mystery (fish come when they come). It validates both meditation practitioners (patient waiting) and workaholics (daily practice). It’s a both/and metaphor in an either/or world.

The Pressure Layer: Forces That Shaped the Fishing Frame

Why fishing specifically? Why not hunting birds or gathering mushrooms? Let’s identify the pressures that made this exact metaphor stick.

Pressure 1: The Commodification of Creativity (Post-Industrial)

The 20th century transformed creativity from rare genius to expected competency. Advertising agencies needed ideas on demand. Studios required scriptwriters to produce. The “creative class” emerged as an economic category.

This created an anxiety: How do you reliably produce something unreliable?

Fishing metaphors offered comfort. Professional fishermen don’t catch fish every time, but their expertise increases odds. The metaphor allowed creativity to be:

Professionalization (technique matters)

Probabilistic (not guaranteed, but improvable)

Respectable (fishing is skilled labor, not lazy waiting)

Compare to farming (too controllable—you plant, it grows) or hunting (too aggressive—stalking, killing). Fishing balanced commercial needs with creative unpredictability.

Pressure 2: Post-Religious Spirituality’s Need for Secular Metaphors

As religious frameworks declined in the West (especially 1960s-70s), creative people still experienced inspiration as transcendent—coming from beyond conscious will. But saying “God gave me this idea” became culturally awkward.

The ocean metaphor provided a secular sacred. The unconscious/collective unconscious became the divine source, reframed in psychological language. Fishing for ideas allowed spiritual experience without religious commitment.

Cultural bias embedded: This is Western appropriation of Buddhist metaphors (mind as water) stripped of Buddhist metaphysics (no-self, dependent origination). The metaphor retained the practice (meditative waiting) but deleted the worldview (dissolution of ego).

Eastern traditions use fish metaphors differently: thoughts are fish passing through awareness, which you observe without grasping. Western creativity culture flipped it: you want to catch the fish. This reversal reveals Western goal-orientation even in supposedly receptive practices.

Pressure 3: Information Theory & Cognitive Science (1950s-1980s)

Shannon’s information theory (1948) described communication as signal extraction from noise. Cognitive science’s “computational theory of mind” (1960s-80s) framed thinking as information processing.

This created a new pressure: Ideas must be extractable from information environments.

Suddenly, the mind wasn’t just an ocean—it was an ocean of data. Fishing became apt because it’s selective extraction. You don’t drink the ocean; you catch specific fish. You don’t process all information; you hook specific ideas.

Neuroscience added anatomical support: the Default Mode Network (discovered 2001) activates during mind-wandering, like drifting in mental currents. “Aha!” moments correlate with gamma-wave bursts—fish breaking the surface.

Technical constraint: Early computers couldn’t search all possibilities (combinatorial explosion). AI researchers developed “heuristic search”—sampling promising areas rather than exhaustive searching. This is... fishing in solution space.

The metaphor fit the computational zeitgeist: Ideas aren’t created from nothing; they’re selected from vast possibility spaces.

Pressure 4: The Self-Help Industry’s Democratization of Genius (1980s-Present)

The self-help boom (culminating in books like “Big Magic” and “The Artist’s Way”) needed to tell millions of ordinary people: “You too can be creative!”

But if creativity is rare genius, most people are excluded. The fishing metaphor democratized it:

Anyone can fish (creativity isn’t just for Mozart)

Better technique helps (teachable, purchasable—buy this book!)

The ocean is abundant (infinite ideas available, not zero-sum competition)

This market pressure shaped the metaphor toward optimism and accessibility. Notice: no one says “ideas are like deep-sea drilling” (too difficult, expensive, expert-only).

Pressure 5: Attention Economy & Digital Distraction (1990s-Present)

The internet created infinite information streams. Social media made everyone a content creator. The pressure became: How do you find signal in noise? How do you have original thoughts when drowning in others’ ideas?

The fishing metaphor evolved: Now you’re fishing in polluted waters (too much information). Meditation/deep work advocates (Cal Newport, etc.) prescribe “going deeper”—diving below the churning surface (Twitter, email) to quieter depths where bigger fish swim.

This is David Lynch’s exact framing: shallow water = small fish (derivative ideas), deep water = big fish (original visions).

The pressure created the need for DEPTH in the metaphor, not just fishing itself.

Cross-Domain Fossil Pattern 1: Optimal Foraging Theory

To understand why the fishing metaphor works cognitively, let’s excavate an unexpected parallel from evolutionary biology.

Optimal Foraging Theory (MacArthur & Pianka, 1966) describes how animals maximize energy intake while minimizing search costs. Key insights:

Patch selection: Forage in rich patches, abandon depleted ones

Giving-up time: Know when to stop searching one area and move to another

Diet breadth: In abundant environments, be selective; in scarce ones, take anything

Now apply this to ideation:

Patch selection: Choose fertile mental domains (areas you know deeply, current problems)

Giving-up time: Abandon unproductive thought-trains (don’t force bad ideas)

Diet breadth: In brainstorming (abundant mode), capture everything; in refinement (scarcity mode), be selective

The fossil pattern: Foraging and fishing are both search strategies in patchy environments with uncertain payoffs. Our brains evolved foraging strategies, then recruited them for abstract “idea foraging.”

Neuroscience confirms this: The same dopaminergic reward circuits activated by finding food activate when solving problems (Schultz, 1998). “Aha!” moments literally feel like catching prey.

What this reveals: The fishing metaphor isn’t arbitrary—it maps onto evolutionary cognitive machinery. We understand idea-generation through foraging because our brains ARE foragers repurposed for abstraction.

Cross-Domain Fossil Pattern 2: Signal Processing & Information Theory

Claude Shannon’s foundational insight (1948): Communication is extracting signal from noise. The ratio matters—too much noise, the signal is lost.

This creates a precise parallel:

Fishing:

Signal = fish

Noise = empty water

Detection = bite on the line

Extraction = reeling in

Ideation:

Signal = valuable idea

Noise = mental chatter, irrelevant thoughts

Detection = recognition (”that’s interesting!”)

Extraction = developing the idea (writing, sketching, prototyping)

But here’s the buried insight: In information theory, you improve signal-to-noise ratio by:

1. Filtering (remove noise frequencies)

2. Amplification (boost signal strength)

3. Repetition (signal consistent across time, noise isn’t)

Applied to ideas:

1. Filtering = meditation/focus (remove mental noise)

2. Amplification = attention (when an idea appears, focus on it)

3. Repetition = persistent ideas (ideas that keep surfacing are signal; fleeting ones are noise)

This is exactly how David Lynch describes it: “Ideas that keep coming back are the big fish.”

What this fossil pattern reveals: The fishing metaphor encodes information-theoretic wisdom that predates information theory. Humans intuitively understood signal extraction before Shannon formalized it.

Cross-Domain Fossil Pattern 3: Quantum Mechanics & The Observer Effect

Here’s a surprising excavation: The fishing metaphor parallels quantum measurement problems.

In quantum mechanics, particles exist in superposition (multiple states simultaneously) until observed—then they “collapse” into one state. The act of observation changes what’s observed.

Parallel in ideation:

Superposition: Pre-conscious ideas exist in potential, vague, multiple-possibility states

Observation: Bringing idea to consciousness (catching it) forces it into specific form

Collapse: The moment you articulate an idea, it loses other potential forms

Notice: Fish underwater are Schrödinger’s fish—you don’t know what you’ve caught until it surfaces. The act of pulling it up (conscious articulation) reveals what it is, but also changes it (from living process to caught object).

This explains a common creative frustration: “The idea felt profound in my mind, but when I wrote it down, it seemed mundane.”

The fishing metaphor captures this: The act of catching transforms what’s caught.

Quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg (1958) actually used fishing metaphors for quantum observation: “We have to remember that what we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.”

The buried connection: Both fishing and quantum measurement involve interactive extraction—you can’t observe without changing.

Evolution Layer: How the Metaphor Mutated Across Disciplines

Let’s track the fishing metaphor’s cross-domain journey.

Phase 1: Buddhist Mind-Training (Ancient Origins)

Original form: Thoughts are fish swimming through the ocean of consciousness. You don’t catch them—you observe them pass. The goal is non-attachment.

Key principle: The ocean (awareness) is not the fish (thoughts). Don’t identify with passing mental phenomena.

Phase 2: Romantic Depth Psychology (Late 19th-Early 20th Century)

Mutation: The unconscious is an ocean. Creative insights are fish rising from depths. You don’t control when they surface, but you can prepare to receive them.

Key shift: From observation (Buddhist) to reception (Romantic). Ideas are gifts from the deep self.

Phase 3: Creative Methodology (Mid-20th Century)

Mutation: You can fish for ideas through technique (meditation, morning pages, incubation). Active-passive synthesis.

Key shift: From pure reception to skillful invitation. You create conditions for ideas to appear.

Phase 4: Cognitive Science (Late 20th Century)

Mutation: “Ideation as search through problem-space.” Fishing becomes sampling in high-dimensional solution spaces. Heuristics are fishing strategies.

Key shift: Mechanistic/computational. The mysticism evaporates; fishing becomes algorithm.

Phase 5: Information Economy (Late 20th-Early 21st Century)

Mutation: Fishing in **data streams**. Information overload means ideas must be extracted from torrents of input. Curation becomes fishing.

Key shift: From internal (unconscious) to external (information environments). You fish in Twitter, research papers, conversations—not just your own mind.

Phase 6: AI & Prompt Engineering (2020s-Present)

Current mutation: Prompting AI is fishing. You cast prompts (bait) into the model’s latent space (ocean) and see what surfaces. The quality of your prompt determines your catch.

Key shift: The ocean isn’t your mind OR external information—it’s a trained model’s parameter space. Ideas exist in 175 billion-dimensional spaces (GPT-3). You’re fishing in alien oceans.

Pattern Across Mutations:

Each phase preserved the core structure (patient waiting + skillful preparation) but shifted:

Location: Internal psyche → external information → AI latent space

Agency: Passive observation → active-passive synthesis → algorithmic optimization

Metaphysics: Spiritual → psychological → computational

The metaphor persisted because its structure (selective extraction from abundant-but-hidden possibilities) maps onto recurring problems, even as the substrate changed.

What the Metaphor Hides: The Archaeological Gaps

Every metaphor illuminates some aspects while obscuring others. What does fishing HIDE about ideation?

Hidden Aspect 1: Ideas as Collaborative Networks

Fishing is solitary. But most ideas emerge from conversation, collaboration, collective intelligence. The lone genius fishing for ideas is a myth.

Better metaphor: Mycorrhizal networks. Ideas are mushrooms (visible fruiting bodies) connected to vast underground fungal networks (conversations, cultures, accumulated knowledge). You don’t catch mushrooms; you participate in networks that fruit ideas.

This reveals the individualist bias in creativity culture. Fishing metaphors serve the “original genius” narrative, hiding how ideas are actually co-created.

Hidden Aspect 2: Ideas as Iterative Construction

Fish exist before you catch them. But many ideas don’t pre-exist—they’re constructed through sketching, writing, prototyping. The process creates the idea, not reveals it.

Better metaphor: Coral reefs. Ideas accrete incrementally, each thought depositing layers on previous thoughts until a structure emerges.

The fishing metaphor misleads when it suggests ideas arrive whole (catch!), obscuring the messy, iterative reality.

Hidden Aspect 3: Ideas as Recombination

Fish are discrete entities. But ideas are often mashups, analogies, cross-pollinations—combinations of existing elements in novel patterns.

Better metaphor: Genetic recombination. Ideas are offspring of parent concepts, inheriting traits, mutating, creating variety.

Fishing metaphors don’t capture this generative recombination.

Hidden Aspect 4: The Role of Constraint

Fishing suggests abundance (ocean full of fish). But creativity often requires constraint, limitation, scarcity. Twitter’s 280-character limit, haiku’s 5-7-5 structure, a fixed deadline—constraints generate ideas.

Better metaphor: Mining in narrow shafts. Constraints force you to dig in specific directions, discovering resources you’d miss in open foraging.

The fishing metaphor’s abundance framing hides how limitation sparks creativity.

The Pressure That’s Changing It Now: AI as Collaborative Ocean

We’re currently witnessing a **mutation event** in real-time.

With AI systems like GPT-4, Claude, Midjourney, the fishing metaphor is adapting:

Old model: You fish in your own mind (or external information you curate).

New model: You fish in AI latent spaces—oceans of compressed human knowledge you didn’t create and can’t fully comprehend.

This creates new pressures:

Pressure 1: Credit & Authorship

If you prompt an AI and it generates an idea, who caught the fish? You (for crafting the prompt)? The AI (for surfacing the response)? The training data (where the “fish” originated)?

The fishing metaphor breaks down because the ocean now contains pre-existing human thoughts (training data), not primordial creative potential.

Pressure 2: Fishing in Alien Waters

AI latent spaces are high-dimensional, non-human representational systems. You’re fishing in 175-billion-dimensional oceans. The fish you catch might look Earth-like but formed in utterly alien conditions.

This challenges the fishing metaphor’s assumption: that the ocean is YOUR unconscious (or a shared human collective unconscious). Now it’s a synthetic ocean.

Pressure 3: Infinite Abundance

If AI can generate endless ideas on demand, what happens to the metaphor’s scarcity element (patient waiting, rare fish)?

The new pressure: Not finding ideas, but **selecting among infinite generations**. Fishing becomes trawling—you catch tons, then sort through the haul.

Archaeological prediction: The fishing metaphor will mutate toward curation/gardening metaphors. The skill shifts from catching to selecting, nurturing, combining what AI generates.

Synthesis: The Archaeological Stack of “Ideas Are Like Fish”

Let’s reconstruct the complete stack:

Evolution Layer:

Buddhist observation → Romantic reception → Creative methodology → Cognitive search → Information curation → AI prompt engineering

⇅ shaped by

Pressure Layer:

Commodification of creativity + post-religious spirituality + information theory + self-help democratization + attention economy + AI emergence

⇅ drove

Intent Layer:

Solve the active-passive paradox of creativity instruction; validate both discipline and surrender; make creativity teachable yet mysterious

⇅ determined

Context Layer:

Depth psychology (Freud/Jung) + Eastern philosophy influx (1950s-60s) + meditation boom (1960s-70s) + computational cognitive science (1960s-80s)

⇅ produced

Artifact Layer:

Widespread metaphor in creativity literature, meditation teaching, cognitive science, innovation consulting

The Stack Reveals:

“Ideas are like fish” isn’t a timeless truth about creativity. It’s a 20th-century solution to historically specific pressures: how to talk about creativity in a post-religious, psychologically-informed, commercially-driven culture that needed to mass-produce inspiration.

The metaphor encoded deep wisdom (search strategies, signal extraction, patient readiness) that predated its formalization, making it feel “naturally” true. But that feeling is itself an artifact—evolved cognitive machinery (foraging instincts) resonating with an apt metaphor.

For Beginners: Why This Matters

If you’re new to thinking about thinking, here’s what this excavation reveals:

When someone tells you “ideas are like fish”:

They’re describing a specific mode (receptive-yet-prepared), not the only mode. Sometimes ideas need aggressive pursuit, collaborative brainstorming, or systematic iteration—not fishing.

They’re inheriting a metaphor shaped by mid-20th-century psychology, Buddhist popularization, and creativity commodification. It’s culturally specific, not universal.

They’re highlighting signal extraction (finding valuable ideas in noisy mental/informational environments) and probabilistic success (technique improves odds but doesn’t guarantee catches).

They’re using evolved foraging intuitions to understand abstract ideation. Your brain finds this metaphor compelling because it activates ancient search-and-reward circuits.

When you USE the fishing metaphor yourself:

Go deep (study your domain thoroughly—this is where big ideas live)

Prepare your gear (develop your craft so you recognize good ideas when they appear)

Be patient (don’t force; creative pressure often backfires)

Stay alert (when an idea bites, pay attention immediately—write it down)

Know when to move (if a mental area is depleted, explore elsewhere)

But also know when NOT to fish:

When you need collaboration (talk to people; co-create)

When you need iteration (build prototypes; refine through making)

When you need constraint (set limitations; force creative problem-solving)

When you need recombination (mash up existing ideas; create analogies)

The fishing metaphor is one tool in your creative toolkit—powerful but not universal.

Meta-Archaeological Insight: What We’ve Unearthed

By excavating “ideas are like fish,” we’ve discovered:

Metaphors are cultural technologies. They’re invented/adapted to solve specific problems at specific times. This one solved: “How do we teach creativity in a secular, commercial, psychologically-informed age?”

Successful metaphors map onto evolved cognition. Fishing works because our brains evolved foraging strategies that transfer to abstract search.

Metaphors encode their creation pressures. The individualism, abundance-framing, and active-passive balance in “ideas as fish” reveal mid-20th-century Western values.

Metaphors hide as much as they reveal. Fishing obscures collaboration, construction, recombination, and constraint—all crucial to ideation.

Metaphors evolve with technology. AI is currently mutating this metaphor from “fishing in your unconscious” to “prompting synthetic oceans.”

The deeper revelation:

When you say “ideas are like fish,” you’re not describing objective reality. You’re participating in a **metaphorical tradition** that emerged from specific historical conditions, encoded specific cultural values, and is currently undergoing AI-driven transformation.

The metaphor feels true not because it IS true, but because it’s **fit for purpose**—and because human cognition is built on evolutionary foraging patterns that resonate with aquatic search metaphors.

This archaeological perspective gives you power: You can choose when to fish, when to garden, when to build, when to collaborate. You’re not trapped by the metaphor—you understand its origins, its purposes, and its limits.

The ultimate insight:

Every time you use a metaphor for thinking about thinking, you’re swimming in history. The fish metaphor is itself a fish—caught from depths of Buddhist philosophy, Jungian psychology, information theory, and evolutionary cognition, now surfacing in your mind.

To understand creativity, sometimes you need to understand the metaphors that shape how you search for understanding.

That’s cognitive archaeology.

And that’s the big fish.

References:

1. Lynch, D. (2006). Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

2. Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

3. Freud, S. (1899). _The Interpretation of Dreams._ Vienna: Franz Deuticke.

4. MacArthur, R. H., & Pianka, E. R. (1966). On optimal use of a patchy environment. The American Naturalist, 100(916), 603-609.

5. Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379-423.

6. Schultz, W. (1998). Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology, 80(1), 1-27.

7. Raichle, M. E., et al. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 676-682.

8. Gilbert, E. (2015). Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear. New York: Riverhead Books.

9. Pressfield, S. (2002). The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles. New York: Black Irish Entertainment.

10. Heisenberg, W. (1958). Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science. New York: Harper & Row.